MHH researcher, with an international research team, has modelled a rare developmental disorder using human brain organoids.

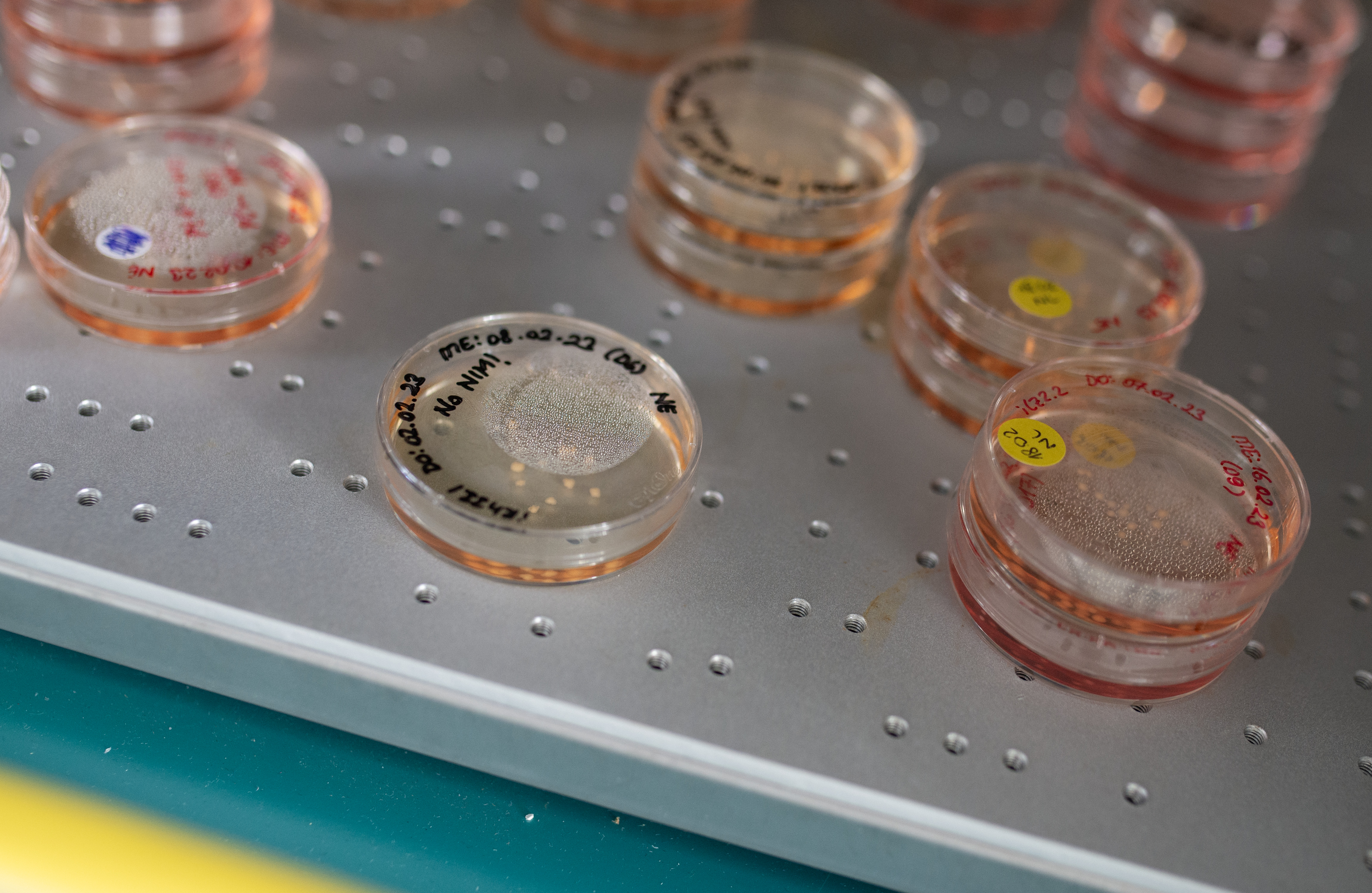

Hirnorganoide verschiedener Entwicklungsstadien im Kulturmedium in einem Brutschrank. Copyright: Karin Tilch

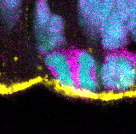

A dividing cell of a human brain organoid. Copyright: Indra Niehaus/MHH

Why do some children develop a brain that is too small (microcephaly)? An international research team involving the German Primate Center - Leibniz Institute for Primate Research (DPZ), Hannover Medical School (MHH) and the Max Planck Institute of Molecular Cell Biology and Genetics has used human brain organoids to investigate how changes in important structural proteins of the cell lead to this severe developmental disorder (EMBO Reports).

Mutations in actin genes alter the way in which early progenitor cells divide in the brain. As a result, the number of these cells decreases, causing the brain to grow less and remain smaller. "For the first time, our findings provide a cellular explanation for microcephaly in people with the rare Baraitser-Winter syndrome," says Indra Niehaus, first author of the study and research associate at Hannover Medical School.

A disorder in the "inner cell scaffold" alters brain development

Actin is a basic building block of the cytoskeleton, i.e. the inner support and transport structure of every cell. People with Baraitser-Winter syndrome carry a single gene mutation in one of two central actin genes. To investigate the effect of these mutations, the researchers generated induced pluripotent stem cells from skin cells of Baraitser-Winter syndrome patients. From these, they formed three-dimensional brain organoids that mimic important steps in early human brain development.

The results were clear: after thirty days of growth, the patient organoids were around a quarter smaller than the control organoids from healthy donors. The inner ventricle-like structures, in which the precursor cells are located and form early nerve cells, were also significantly smaller.

Fewer stem cells in the early brain

A closer look at the cell types in the organoids revealed a shift: the proportion of apical progenitor cells, i.e. the central progenitor cell population of the cerebral cortex, was significantly reduced. At the same time, more basal progenitor cells, a type of daughter cell that normally only appears later in development, were formed.

Cell divisions tilt in the wrong direction

Using high-resolution microscopy, the team analyzed the division of the apical progenitor cells. Normally, these cells divide predominantly perpendicular to the surface of the ventricular zone. Only in this way are the cell components evenly distributed and two new apical progenitor cells are formed. In the patient organoids, precisely this process was disturbed: the proportion of vertical divisions was massively reduced. Instead, the majority of cells divided horizontally or at oblique angles. This altered orientation led to the apical progenitor cells renewing themselves less frequently, detaching more often from the ventricular zone and transforming into basal progenitor cells.

"Our analyses show very clearly that an altered division orientation of the progenitor cells is the decisive trigger for the reduced brain size," says Michael Heide, group leader at the German Primate Center and last author of the

study. "A single change in the cytoskeleton is enough to significantly alter the course of early brain development."

Subtle structural deviations with major consequences

Electron microscope images revealed further abnormalities: The cell shapes in the ventricular zone were irregular. There were more protrusions between neighboring cells. In addition, there was an unusually large amount of tubulin, another building block of the cytoskeleton that plays an important role in cell division, at the cell junctions. Although the basic cell architecture was still recognizable, these changes could be sufficient to permanently disrupt the direction of cell division.

Genetic evidence: a single mutation is enough

To rule out the possibility that differences between patient and control organoids were due to other genetic factors, the team carried out a control experiment: The healthy stem cell line was modified with CRISPR/Cas9 so that it carried exactly the same mutation as one of the Baraitser-Winter syndrome patients. The result: the brain organoids generated in this way showed the same malformations as the patient-derived organoids - proof that the mutation itself is the cause.

What does this mean for medicine and research?

"Our results help to understand how rare genetic diseases can cause complex brain malformations and they show the potential of brain organoids for biomedical research," says Michael Heide. "The therapeutic potential of this study lies in diagnostics, as our data helps to better classify genetic findings in patients. Since the disease affects early fetal development processes, interventions in humans would be complex. However, new drugs that influence the interaction of actin and microtubules,

could open up new approaches in the long term," says Nataliya Di Donato, Director of the Institute of Human Genetics at Hannover Medical School.

Text: DPZ/MHH