MHH nephrologists find cells that provide information about the function of the kidney transplant after rejection.

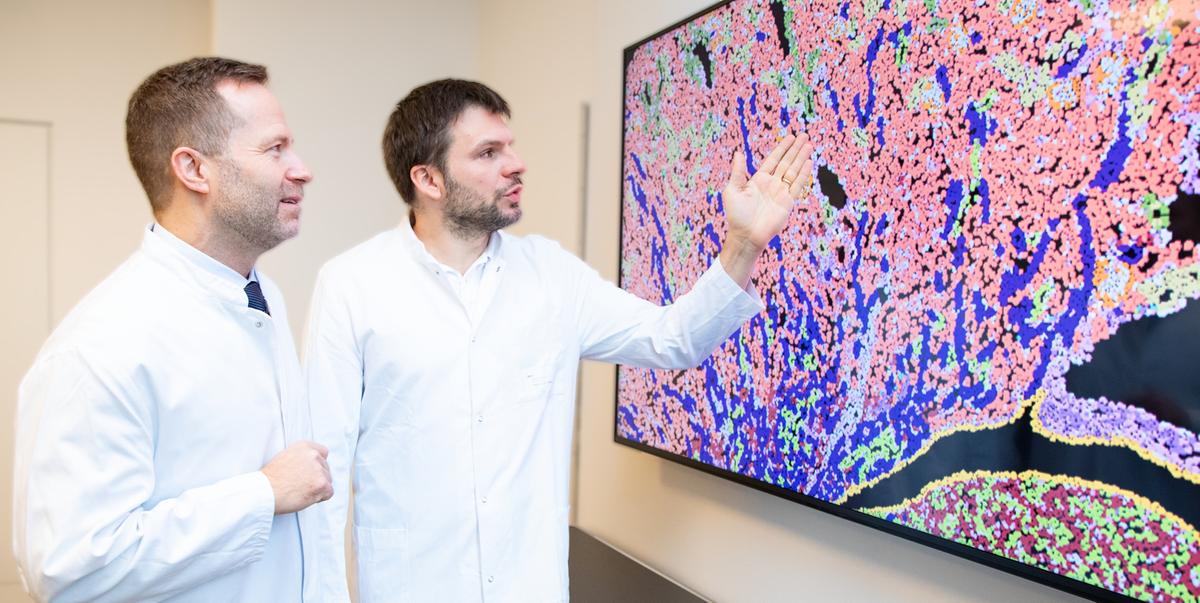

Prof. Dr. Christian Hinze (right) and Prof. Dr. Kai Schmidt-Ott discuss the results of spatial gene expression analyses of a transplanted kidney that shows signs of rejection. Copyright: Karin Kaiser/MHH

A research team led by Prof. Dr. Christian Hinze, senior physician at the Hannover Medical School's (MHH) Clinical Departmentof Nephrology and Hypertension, has gained new insights into the treatment of kidney transplant patients. The team has discovered properties of kidney cells that indicate how well a transplant recovers in the long term after rejection. "The transplant itself develops a kind of molecular memory of the rejection," says Professor Hinze. "The specific cell states we have identified can tell us how well the kidney actually recovers. This makes them promising candidates for future diagnostic tools," says Professor Hinze, who is responsible for the follow-up care of kidney transplant patients at the MHH, among other things. The results were published in the journal Nature Communications.

Acute rejection causes the transplant to gradually lose its function

Acute rejection remains one of the main causes of kidney transplant failure, although it is treatable. Immune cells, known as T cells, recognize the transplant as foreign. They migrate into the organ, trigger inflammation and damage the tissue. If this process is not stopped with medication, the organ gradually loses its function.

Cells differ from healthy cells

Professor Hinze's research team, together with cooperation partners from Charité Berlin and the Alberta Transplant Applied Genomics Centre in Canada, investigated how the tissue of a transplanted kidney changes during and after such T-cell-mediated rejection. They showed that it is not only the immune cells that play a role, but above all the reaction of the cells of the renal tubule. The cells of the fine tubular system are responsible for central transport processes and react to rejection with conspicuous stress and repair patterns. "Some of these cell states are clearly different from healthy cells," explains Professor Hinze. "Some of them do not disappear even after successful treatment of the rejection and occur particularly when the transplant has a high risk of failing later on."

Large patient cohorts have shown that a high proportion of such cells in the biopsy can be a warning sign - an indication that the transplant is at risk in the coming years.

"For physicians, this opens up a new possibility to assess risks after rejection more accurately and to plan follow-up care more individually," says Prof. Dr. Kai Schmidt-Ott, Director of the MHH Clinical Department of Nephrology and co-author of the study. "The research results could help us to identify kidney transplant patients who require a change in therapy or particularly close monitoring. And perhaps - as future studies will have to show - the newly discovered cellular programs can even be influenced therapeutically at some point."

In their work, the researchers combined data from experimental models, single-cell analyses, spatial gene expression and extensive biopsy collections. This resulted in a comprehensive picture of how tubular cell states develop, how they are distributed in the tissue and what significance they have for long-term progression. For the MHH, one of Europe's leading transplant centers, the results are a further step towards more precise, future-oriented transplant medicine.

You can find the original publication here.

Text: Administrative Unit Communications