A new kidney for Bettina

50 years ago: German premiere at Hannover Medical School / 800 kidney transplants in children and adolescents at the MHH since then

1970 - a year of new beginnings for transplant medicine in Germany. The transplant pioneers at the MHH were faced with difficult decisions: should the still quite young procedure of organ transplantation not only benefit adults, but also children and adolescents?

Bettina S. had been ill all her life; the 13-year-old Hanoverian was born with so-called shrunken kidneys. This meant constant hospitalization and finally, when her kidneys finally failed, constant dependence on life-saving dialysis to remove toxins from her body. The complete kidney failure had also caused her blood pressure to rise dramatically. The diseased kidneys had to be removed.

Dialysis determined Bettina's life. Her blood was purified three days a week. The rest of the time, her body recovered from the strain of the blood wash. Bettina was no longer able to go to school. In addition, her "shunt" kept causing problems. The specially created fistula between the artery and vein, to which the dialysis machine was connected, threatened to close. Bettina became weaker and weaker and lost her courage to face life. She later recalled that her dependence on dialysis was particularly hard on her. Her parents and physicians were worried about her life.

Transplantation was uncharted medical territory

In 1970, kidney transplants were still uncharted medical territory. It had only been 20 years since the first successful kidney transplant between identical adult twins in the USA. In the meantime, the operation had been improved and introduced by several Clinical Departments worldwide. Organs from brain-dead donors were also available. However, in order to ensure the function of the organ, which was foreign to the body, the immune system of the organ recipient had to be suppressed for the rest of his or her life. Immunosuppressive substances (e.g. cortisone, azathioprine) were available for this purpose and had proven their worth in clinical trials.

The conditions for transplant medicine were favorable at Hannover Medical School, which was founded in 1963. In 1969, the Clinical Department for Abdominal and Transplant Surgery was founded under the direction of Prof. Dr. Rudolf Pichlmayr. A year earlier, he had been appointed to the MHH by the Ludwig Maximilian University of Munich and brought with him extensive experience from scientific and clinical work on organ transplantation.

The first kidney transplant in an adult at the MHH took place in 1968. It was not a success; the kidney was rejected soon after the transplant. "The big problem in the early years was the extreme risk to patients from the concomitant therapy that was common at the time. The concept was to prevent rejection reactions through the highest possible immunosuppression," recalled Prof. Pichlmayr, who died in 1997, in a newspaper report in 1991. Later - in the 1980s - there was a switch to the new drug Ciclosporin and combination therapies, which allowed a better balance between sufficient immunosuppression and the risk of infection. But in 1970, the physicians were faced with the question: is kidney transplantation a treatment procedure that should also be attempted in children?

As Bettina's condition worsened and she no longer wanted to endure the hardships of dialysis, the pediatricians and surgeons, together with her family, decided to transplant a donor organ from another donor. "There was no other chance for our daughter," said Bettina's mother at the time. Then the time of waiting began. Bettina later recalled that, surprisingly, she felt no fear of the procedure. She had come to terms with life on dialysis.

The wait came to an end at the beginning of December 1970. A young man had died in an accident in a town in southern Germany; his kidney "fit" and was released for transplantation by his relatives. Bettina survived the operation well. Due to the immunosuppressive medication, she was at high risk of infection and had to spend four weeks in quarantine. She only got to see her family through a window. She was preoccupied with one thought in particular: Would the new organ actually work? What a relief when the urine started flowing again!

Better development opportunities, higher quality of life

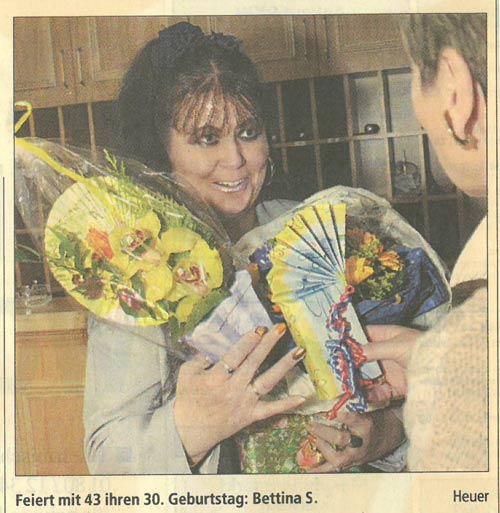

The year 1970 fundamentally changed Bettina's life. She grew into a young woman and found an apprenticeship. This was not easy at first. Unfortunately, when she talked about her medical history, offers were usually not forthcoming, possibly out of fear of illness-related absences or frequent visits to the physician. Taking medication for many years made her eyesight and hearing worse, so she had to give up her job and became an early retiree and housewife. But the kidney lasted almost 50 years. Bettina S. - who is now 64 years old - has been back on dialysis for three years.

After this first successful pioneering act, other young patients quickly followed, with equally good results. Kidney transplantation established itself as the preferred treatment for chronic kidney failure. Around 800 children and adolescents benefited from an expansion of the transplant program at the MHH over the following 50 years. Clinical Departments in Germany and abroad followed suit.

"The pediatricians and surgeons soon experienced that children and adolescents had a much higher quality of life after transplantation than on dialysis," says Prof. Dieter Haffner, today Director of the Clinical Department for Kidney, Liver and Metabolic Diseases. "After the transplant, the children show significantly better growth and cognitive performance, which is particularly noticeable in learning, and thus have a chance to develop normally." This is why children are given preference when Eurotransplant allocates donor kidneys from deceased donors. Meanwhile, the organs often come from the parents: by donating a kidney, they save their children waiting time and give them a better chance in life.

Annette Tuffs / Jill Kaltenborn