MHH researchers discover sugar structures on kidney cells that can predict the response to treatment with immune checkpoint inhibitors.

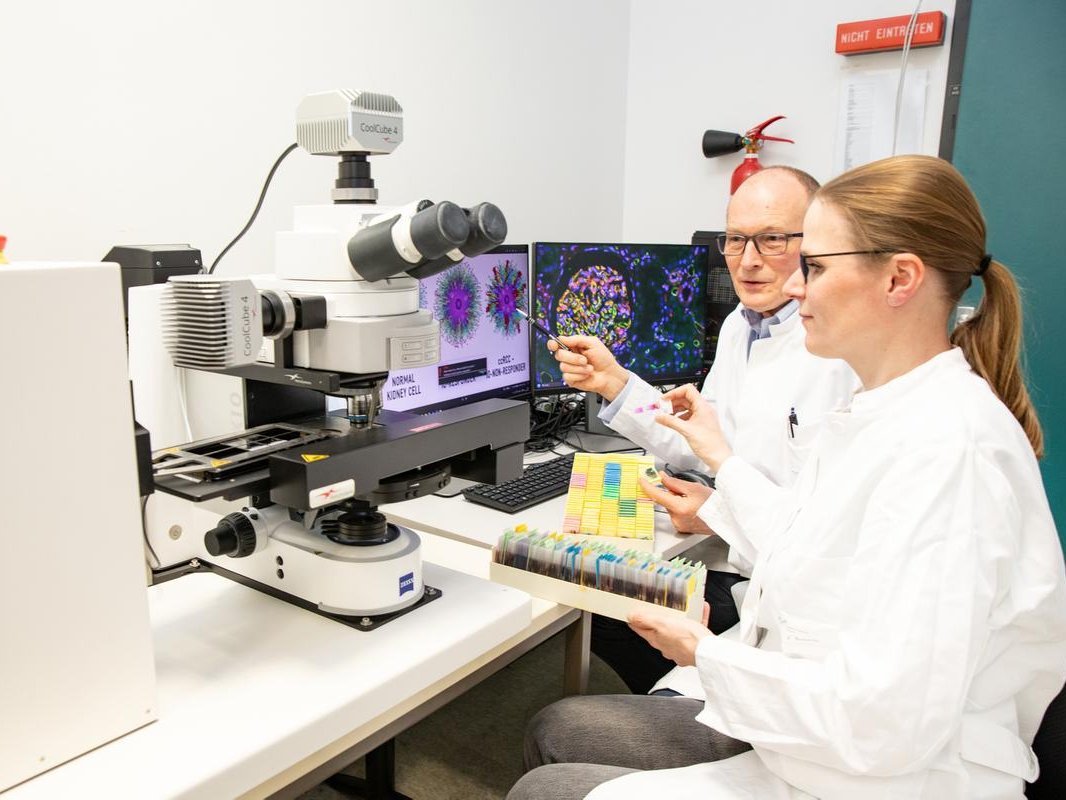

Prof. Dr. Jan Hinrich Bräsen and Jessica Schmitz used a fully automated high-tech microscope to examine the sugar structures on kidney tissue. Copyright: Karin Kaiser/MHH

Among modern cancer therapies, the so-called immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICI) are among the most successful treatment methods. These antibodies activate the immune system and enable the T immune cells to detect and destroy tumor cells. Immune checkpoint inhibition is also an important part of treatment for clear cell renal cell carcinoma (ccRCC), the most common form of kidney cancer. It is used when metastases have already formed and surgery alone cannot control the cancer. However, the treatment is not only expensive, it also has side effects. In addition, not all patients respond to immunotherapy. However, there is currently no way of predicting which patients with ccRCC will actually benefit from ICI.

A research team led by Prof. Dr. Jan Hinrich Bräsen, managing director at the Institute of Pathology and medical director of the Nephropathology working group at Hannover Medical School (MHH), has now identified biomarkers that could answer this question. While many researchers focus on genes or proteins in their search for such biological fingerprints, the nephropathologist has focused on a completely different group of substances: Sugar. In a study, the research team discovered two sugar structures that can be used to make personalized predictions about who will respond to ICI treatment and who will not. These biomarkers could serve as a guide for individualized treatments and minimize unnecessary ICI therapies.

ICI lifts the camouflage of tumor cells

Our body's own immune system is active around the clock to fight pathogens and eliminate abnormal cells before they can develop into malignant tumors. However, cancer cells have various tricks up their sleeve to hide from the immune system. One of them involves the T cells of the immune system, which are actually supposed to detect tumor cells. They do this with the help of certain receptors on their surface, the immune checkpoints. These work according to the lock-and-key principle, so that the T cells can distinguish the body's own healthy cells from diseased and malignant ones. As checkpoints, the immune checkpoints then slow down or activate the immune defense accordingly. Cancer cells use this protective mechanism by binding to the checkpoints like healthy body cells and disguising themselves as harmless cells, so to speak. In this way, they escape the immune system's grasp. Immune checkpoint inhibitors block the binding of checkpoint proteins to their partner proteins on the cancer cells. This prevents the switch-off signal and cancer cells become visible to the T-cells again.

Greater diversity of sugar structures than genetic diversity

Why this mechanism does not work in the same way in every person with ccRCC is still a mystery. The research team suspected that sugar structures could play a role. "Every cell in our body contains a jungle of sugar structures, so to speak, which must have some kind of function," says Professor Bräsen. These look different in every person and have a greater variety than our genetic differences. The sugar compounds, technically known as glycans, exist on all body cells, including kidney cells. In cooperation with a working group at the Medical University of South Carolina (MUSC), the researchers used MALDI imaging mass spectrometry to analyze the sugar compounds. This is an imaging method for analyzing chemical compounds and their spatial distribution in a sample. In addition, tissue sections stained against immune markers and immune cells were scanned almost completely automatically using a motorized high-performance microscope, digitized and evaluated with AI support. "This enabled us to assign these kidney glycans to their respective kidney region, such as renal corpuscles and tubules, and to create a general atlas of sugar distribution in the healthy kidney," says Jessica Schmitz, Scientific Director of the Nephropathology Unit. The researchers compared the cell surfaces in healthy kidneys and ccRCC tumors and analyzed their sugar structures in cooperation with sugar experts from the MUSC.

Sugar biomarkers characterize ICI responders

After removal of the tumor, the patients were treated with ICI. It was noticed that in the group of non-responders, i.e. patients who did not respond to the immunotherapy, two specific types of sugar were found in greater numbers. "These N-glycans are promising biomarker candidates for identifying responders and non-responders even before ICI treatment," says Professor Bräsen. After all, according to associate professor Dr. Philipp Ivanyi, senior physician at the Clinical Department of Haematology, Haemostaseology, Oncology and Stem Cell Transplantation at the MHH, where the patients were treated, up to a third of people with ccRCC tumors are non-responders. They could be spared a complex and expensive immunotherapy - and possible serious side effects that occur when the activated immune system attacks healthy organs. Before the sugar biomarkers find their way into everyday clinical practice, however, they still need to be investigated further.

Text: Kirsten Pötzke

Service:

The original paper "Spatial atlasing of N-glycosylation in healthy control and clear cell renal cell carcinoma tissues linked with immune checkpoint inhibition response by MALDI mass spectrometry imaging" can be found here.